Tagged: George Sturt

Occupations Liberal and Illiberal

Mosaic depicting musicians, from the so-called Villa of Cicero, Pompeii,1st century BCE, signed Dioskourides of Samos.

Wheelwright philosopher George Sturt (see “In The Bones,” below), describing his experience in assisting a master cart-maker in the family shop, says something that many of his readers would have found surprising.

Truly it was a liberal education to work under Cook’s guidance. I never could get axe or plane or chisel sharp enough to satisfy him; but I never doubted, then or since that his tiresome fastidiousness over tools and handiwork sprang from a knowledge as valid as any artist’s (The Wheelwright’s Shop, Cambridge UP, 54).

Equating a manual trade–what Hugh of St. Victor would have called a “mechanical art”– with anything “liberal” runs counter to a tradition dating back to Greece and Rome. “Liberal education” gets its name from the ancient “liberal arts”, disciplines which had more to do with philosophical contemplation than with usefulness, and which were the domain of those privileged people whose economic standing freed them up for the practice of virtue and politics.

In spite of the great cultural distance between them, we may contrast Sturt’s words with Cicero’s discussion of liberal and illiberal occupations in On Duties, his handbook for the conduct of the dignified. Its ranking of occupations was fairly representative of its time, and would prove durable for a long while afterward. Economic historian M. I. Finley calls On Duties “one of the most widely read ethical treatises ever written in the west.” (The Ancient Economy, University of California, 1974, p.42), and whether or not Sturt had direct contact with it, its ideals for the gentleman were still quite influential in Sturt’s England. Here is Cicero:

Now in regard to trades and other means of livelihood , which ones are to be considered becoming to a gentleman (liberales) and which are to be considered vulgar (sordid), we have been taught, in general as follows. First, those means of livelihood are rejected as undesirable which incur people’s ill-will, as those of tax-gatherers and userers. Unbecoming to a gentleman, too, and vulgar are the means of livelihood of all hired workmen (mercinnarriorum) whom we pay for mere manual labor (operae) not for artistic skill (artes emuntur), for in their case the very wage they receive is pledge of their slavery (servitutis). . . . And all mechanics (opificesque) are engaged in vulgar trades (artes) for no workshop can have anything liberal about it. Least respectable are those trades that cater to sensual pleasures:

Fishmongers, butchers, cooks, poulterers,

And Fisherman,as Terence says. Add to these, if you please, the perfumers, dancers, and the whole corps de ballet.

But the professions (artibus) in which either a higher degree of intelligence (prudentia) is required or from which no small benefit (utilitas) to society is derived–medicine and architecture, for example, and teaching–these are proper (honestarum) for those whose social position (ordini) they become.

Against this background, Sturt’s metaphor is striking, though it’s not clear precisely what he meant to convey with it. Perhaps by “liberal” he wanted to indicate the comprehensive nature of the knowledge Cook transmitted in the shop. And he clearly wanted to elevate Cook to the level, at least in terms of skill, of the painters and other “artists” who in the preceding centuries had graduated to the ranks of the “polite.” Since the eighteenth century or so when that social promotion was cemented, Marx and Ruskin had intervened, too, and Sturt was sympathetic to their celebration of labor. His purpose was subversive: Cook’s workshop know-how, while it didn’t count as “science”, was nonetheless ennobling and worthy of admiration. In its attention to the perfection of its object, was it even, maybe, a little like contemplation?

In the Bones

In the early nineteen-twenties, about the time Martin Heidegger was preparing to take aim at intellectualist notions of skilled behavior, George Sturt, a third-generation cart and wagon manufacturer in England, had this to say about the knowledge of his craftsmen:

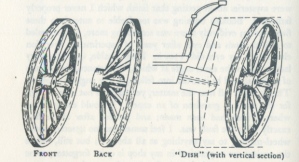

There was nothing for it but practice and experience of every difficulty. Reasoned science for us did not exist. “Theirs not to reason why.” What we had to do was to live up to the local wisdom of our kind; to follow customs, and work to the measurements, which had been tested and corrected long before our time in every village and shop all across the country. A wheelwright’s brain had to fit itself to this by dint of growing into it, just as his back had to fit into the suppleness needed on the saw-pit, or his hands into the movements of that would plane a felloe “true out o’ wind”. Science? Our two-foot rules took us no nearer to exactness than the sixteenth of an inch: we used to make or adjust special gauges for the nicer work; but very soon a stage was reached when eye and hand were left to their own cleverness, with no guide to help them. So the work was more of an art–a very fascinating art–than a science; and in this art, as I say, the brain had its share. A good wheelwright knew by art but not by reasoning the proportion to keep between spokes and felloes; And so too a good smith knew how tight a two-and-a-half inch tyre should be made for a five-foot wheel and how tight a four-foot, and so on. He felt it, in his bones. It was a perception with him. But there was no science in it; no reasoning. Every detail stood by itself, and had to be learnt by trial and error or by tradition. The Wheelwright’s Shop (Cambridge UP, 2000) 19-20.

Heidegger would have understood.